Custom Cars

A Custom Car refers to a passenger vehicle that has been modified in appearance and performance to reflect the owner's unique style and needs. For over 100 years, people have been customizing cars to make them stand out and express their personal identity. The practice of customizing cars has evolved over the last century, blending influences from high-end coachbuilding, grassroots ingenuity, and shifting cultural trends.[1]

In the early days, the term "Custom Car" referred to luxury vehicles commissioned by the wealthy and influential. These cars, often created by renowned coachbuilders like Brunn, Dietrich, or Murphy, were built from scratch or heavily modified on high-end chassis to reflect the owner's unique tastes and needs. These bespoke vehicles symbolized status, combining artistry and craftsmanship with cutting-edge engineering.[1]

At the same time, a more grassroots movement began to emerge, particularly during the economic challenges of the Great Depression in the 1930s. While luxury custom cars remained a hallmark of the elite, everyday people began taking mass-produced cars and making modifications to improve their appearance or performance. Often done on a budget, these changes became known as "Restyled Jobs." Unlike their high-end counterparts, these restyling efforts were accessible and marked the beginning of a do-it-yourself approach that would shape car culture for generations.[1]

By the 1940s and 1950s, the custom car movement had fully taken root in the United States. Enthusiasts began to modify their automobiles not only for personal expression but also for better performance. This era saw the birth of what is now known as Kustom Kulture, where car modifications became both an art form and a lifestyle. Over time, the movement grew into a global phenomenon, inspiring countless automotive subcultures and influencing modern car design and engineering.[1]

Contents

- 1 Early Beginnings: Luxury and Status

- 2 The Great Depression and the Rise of DIY Customizing in the 1930s

- 3 Custom Cars of the 1940s and The Rise of Customizing

- 4 Pioneering Customizers of the 1940s

- 5 Popular Custom Modifications of the 1940s

- 5.1 Chopped Tops

- 5.2 Channeled Bodies

- 5.3 Inset License Plates

- 5.4 Frenched Headlights

- 5.5 Shaved Trim

- 5.6 Solid Hood Sides

- 5.7 Removed Running Boards

- 5.8 Fender Skirts

- 5.9 Custom Bumpers

- 5.10 Spotlights

- 5.11 Cowl-Antenna

- 5.12 Push-Button-Operated Doors

- 5.13 Custom Hubcaps

- 5.14 Custom Grilles

- 5.15 Lowered Suspensions

- 5.16 Carson Tops

- 6 Impact of World War II on Custom Car Culture

- 7 The Post-War Boom and the Lead Sled Era

- 8 Custom Cars of the Early 1950s

- 9 Customizing vs Restyling

- 10 West Coast Restyling of the Early 1950s

- 11 Deck Out

- 12 The Golden Era of the 1950s

- 13 Lowrider and Kustom Kulture of the 1960s and the 1970s

- 14 Modern Custom Cars

- 15 Custom Cars of the 1940s

- 16 Custom Trucks of the 1940s

- 17 Sport Customs of the 1940s

- 18 References

Early Beginnings: Luxury and Status

The term "Custom Car" initially referred to luxury vehicles commissioned by wealthy individuals during the early 20th century. These bespoke cars were built by renowned coachbuilders such as Brunn, Dietrich, and Murphy. Constructed on high-end chassis from automakers like Duesenberg and Packard, they combined artistic craftsmanship with cutting-edge engineering to symbolize status and exclusivity.[1]

The Great Depression and the Rise of DIY Customizing in the 1930s

During the Great Depression, car ownership became a precious luxury. Instead of trading in vehicles for newer models, many Americans, particularly teenagers, opted to modify and improve their existing cars. These grassroots efforts gave rise to what became known as "Restyled Jobs," where modest, mass-produced vehicles were transformed into personalized expressions of style and ingenuity.[1]

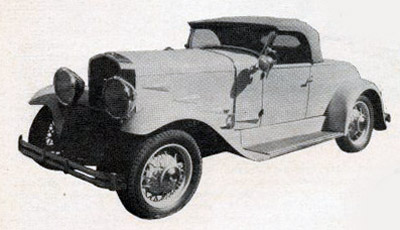

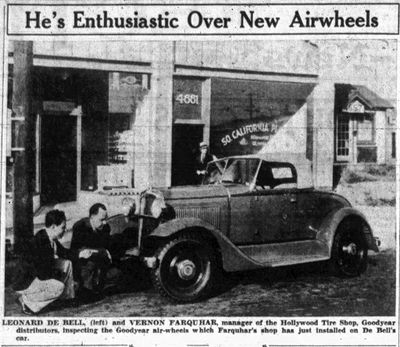

One prominent figure from this period was Frank Kurtis, a pioneer in custom car culture and manager at Don Lee Coach and Body Works.[2] In 1930, Kurtis reimagined his 1928 Ford Model A Roadster with streamlined fenders, a lengthened hood, a custom radiator shell, and Cadillac headlights. His work reflected a new aesthetic focused on smooth lines and subtle modifications, setting the stage for the custom car movement.[3]

Another significant influence on the birth of the custom car trend was George DuVall, a designer and fabricator who is often credited with inventing the first "DuVall-style" V-windshield. This iconic piece, a streamlined windshield with a center divider, became a hallmark of early custom cars and is still celebrated today as a symbol of innovation and craftsmanship. DuVall worked closely with Southern California Plating Co., a business specializing in chrome plating that played an integral role in shaping the look of custom cars during this era. Chrome accents, such as grilles, bumpers, and trim, became a defining characteristic of custom cars, and Southern California Plating Co. supplied much of the work that gave early customs their distinctive, polished appearance.[4]

The 1930s also saw the emergence of streamlining in automotive design, inspired by advances in aerodynamics and the Art Deco movement. This influence encouraged customizers like Kurtis and DuVall to prioritize sleek shapes and futuristic details in their modifications. Streamlining wasn’t just aesthetic—it also appealed to those seeking improved performance, as smooth, flowing lines reduced wind resistance.

Together, these innovators and businesses laid the foundation for what would become a full-fledged cultural movement. Their work in blending form and function established the visual language of custom cars, which would evolve into a lifestyle and artistic tradition that persists today.

Custom Cars of the 1940s and The Rise of Customizing

The 1940s marked a significant turning point in the evolution of custom cars, as the practice of modifying automobiles for aesthetic and performance purposes transitioned from a niche hobby into a full-fledged cultural movement. While the 1930s had laid the groundwork, primarily with luxury coachbuilt customs and grassroots "restyled jobs," the 1940s saw a rapid expansion of customization techniques and the establishment of influential builders who would shape the industry. Figures like Jimmy Summers, Harry Westergard, George Barris, and Bill Hines pioneered key modifications such as chopped tops, shaved trim, fadeaway fenders, and the use of lead for seamless bodywork, setting the stage for the golden age of customs in the following decade.

Customizing in the early 1940s was still an underground practice, primarily concentrated in California, where warm weather and a thriving car culture provided the ideal environment for experimentation. While early custom cars were often modified for aesthetics, they also incorporated elements from race cars, hot rods, and European luxury automobiles.

During this period, automobile manufacturing was halted in 1942 due to the United States' entry into World War II, and materials such as steel, rubber, and fuel were rationed. As a result, car enthusiasts had to rely on modifying older vehicles rather than purchasing new ones. Many returning servicemen, trained in welding, machining, and bodywork, applied their technical skills to automobile customization, fueling a post-war boom in the custom car scene.

Pioneering Customizers of the 1940s

Jimmy Summers

Considered by many to be one of the first professional customizers, Jimmy Summers operated Jimmy Summers Custom Automobile Body Shop at 7919 Melrose Avenue, Los Angeles, throughout the late 1930s and 1940s. His shop was located across from Fairfax High School, where students such as Alex Xydias would watch him work.

Summers was known for his chopped tops, channeled bodies, recessed license plates, frenched headlights, and seamless body modifications that predated many of the factory design trends of the 1950s. Unlike the more radical customizers who followed him, Summers focused on subtle refinements that made stock cars look smoother and more sophisticated.

His work gained recognition among early hot rodders and car enthusiasts, and his techniques helped standardize many of the fundamental modifications that would define kustom kulture.

Harry Westergard

While Summers operated in Los Angeles, Harry Westergard was developing his own unique approach to customizing in Sacramento, California. Working from a garage on Fulton Avenue, Westergard modified cars for local racers and street enthusiasts, often using salvaged parts from high-end luxury automobiles.

Westergard's signature touches included, chopped tops, custom grilles often sourced from LaSalle and Packard models, molded fenders, fadeaway fenders, lowered suspension, smoothed and reshaped body lines.

He was particularly influential in the early Mercury custom scene, setting the groundwork for what would later be known as "lead sleds." Many of his styling cues were adopted and expanded upon by George Barris and Sam Barris in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

George Barris and the Birth of Barris Kustoms

One of the most influential figures in custom car history, George Barris, began his career in Roseville, California, where he learned metal shaping and bodywork. George honed his craft under Harry Westergard before moving to Los Angeles in 1942.

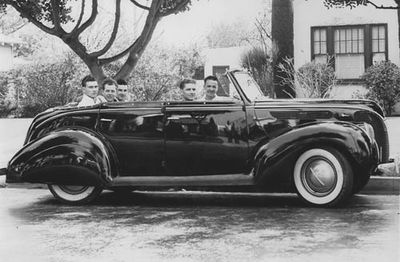

In 1944, Barris opened a small shop on Imperial Highway in Bell, California, officially establishing what would become Barris Kustoms. The details of exactly how Sam Barris joined the business vary depending on the source. According to a 1953 Hop Up article, Sam looked up his long-lost brother after the war, and the two sat down to reminisce about old times. As they laughed about a Buick they had restyled up in Roseville, George suddenly had an idea. "Hey, man, I've got an idea. Let's go into the custom business together!" Sam wasn’t convinced. "I don’t know the first thing about bodywork," he reminded George. But George had confidence in his brother. He started teaching Sam the tricks of the trade and, after a few weeks, decided he was good enough to pass as a bodyman. The brothers pooled their resources and rented a small shop on Imperial Avenue in Los Angeles in 1946. By the late 1940s, Barris had gained national recognition for their radical body modifications, custom paint techniques, and signature styling elements. Their work was prominently featured in the first Hot Rod Exposition Show in 1948, helping to legitimize custom cars as a distinct automotive art form.

Popular Custom Modifications of the 1940s

The 1940s was the decade when signature custom modifications became standard practice. Customizers were perfecting the art of chopping tops, sectioning bodies, and molding body panels to create smoother, more flowing lines. Some of the most popular modifications of the time included:

Chopped Tops

Lowering the roofline of a car for a sleeker, more aggressive stance. One of the most dramatic and defining modifications of the 1940s. Popular among both hot rodders and customizers, a well-executed chop could turn an ordinary sedan into a sinister boulevard cruiser or give a convertible a low, road-hugging profile when paired with a padded Carson-style top.

Channeled Bodies

Also known as “body dropping,” this modification involved lowering the body over the frame rails to achieve a lower stance without altering the roofline. By cutting the floor and raising it higher around the frame, customizers could make a car sit dramatically lower, giving it a ground-hugging, streamlined look. Channeled bodies were popular among both early hot rodders and customizers, who favored a low, aggressive profile that emphasized speed and style.

Inset License Plates

This feature marked the "California Car" back in the early days of customizing. By recessing the license plate into the deck lid or rear pan, builders achieved a cleaner, more integrated look. Eliminating bulky brackets and exposed mounts, inset plates helped create the smooth, flowing lines that became a defining trait of early West Coast Customs.

Frenched Headlights

A signature custom touch born in the 1940s, this modification involved recessing the headlights into the fenders for a flush, integrated look. By eliminating factory bezels and blending the lights into the body, customizers gave their cars a refined, futuristic appearance that remained popular for decades.

Shaved Trim

One of the simplest yet most effective ways to refine a custom car’s appearance. By removing factory badges, door handles, and excess chrome, builders achieved a smooth, uninterrupted look that emphasized the car’s body lines. Often paired with hidden door poppers, this modification gave customs a sleek, almost futuristic presence on the street.

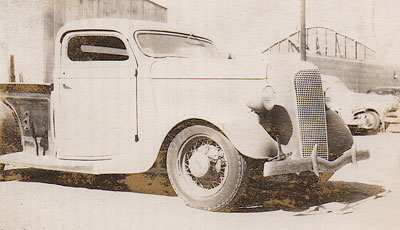

Solid Hood Sides

A classic pre-war custom trick that carried into the 1940s, replacing factory-vented hood sides with smooth, solid panels gave cars a more refined and seamless look.

Removed Running Boards

A popular modification that gave cars a lower, more streamlined profile. By eliminating the running boards and extending the rocker panels, customizers created a sleeker, more upscale appearance reminiscent of high-end coachbuilt cars. This simple yet effective change made early customs look more modern and refined.

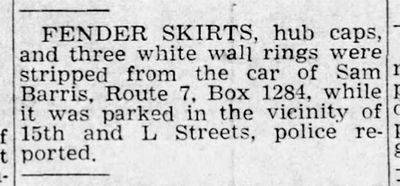

Fender Skirts

A signature custom touch that enhanced a car’s flowing lines by covering the rear wheel openings. Inspired by luxury cars of the era, skirts gave customs a smooth look, making them appear lower and more refined. Often paired with lowered suspensions and wide whitewall tires for maximum effect.

Custom Bumpers

Swapping out factory bumpers for more stylish alternatives was a popular way to personalize a custom. Ripple bumpers and 1940 Oldsmobile bumpers were among the favorites, adding a touch of elegance or a more aggressive stance.

Spotlights

A popular accessory that added both style and function, spotlights became a staple of 1940s customs. Often mounted in pairs on the A-pillars, they gave cars a high-end, almost factory-luxury look. Appleton spotlights were the gold standard, prized for their sleek design and ability to swivel, though most were installed purely for style rather than function.

Cowl-Antenna

A subtle but stylish modification, relocating the antenna to the cowl kept the car’s lines clean while maintaining functionality.

Push-Button-Operated Doors

A high-tech touch for the 1940s, replacing traditional door handles with hidden push-button mechanisms, gave customs a sleek, futuristic look. This modification not only enhanced the car’s smooth, uninterrupted lines but also added an element of mystery and sophistication.

Custom Hubcaps

A must-have accessory in the 1940s, custom hubcaps added flair and individuality to any build. Single-flipper hubcaps were a popular choice.

Custom Grilles

Swapping out stock grilles for more elaborate designs was a signature touch of 1940s customs. Builders often borrowed from Cadillac, LaSalle, or Packard to create a more upscale, distinctive front end. A well-chosen grille could completely transform a car’s personality, giving it a luxurious or aggressive look.

Lowered Suspensions

A key element of the early custom look, lowering a car’s suspension gave it a sleeker, road-hugging stance. This was often achieved by de-arching the leaf springs, a simple but effective method to bring the body closer to the ground. A lower ride height enhanced the car’s streamlined appearance and set it apart from stock models.

Carson Tops

Developed by Amos Carson and perfected by Glen Houser at Carson Top Shop, the Carson Top was a non-folding, padded convertible roof that gave cars a luxurious, sleek profile. It became a defining feature of high-end customs in the 1940s.

Impact of World War II on Custom Car Culture

The outbreak of World War II temporarily halted the progress of the custom car movement as material shortages, fuel rationing, and restrictions on civilian car production made it difficult for enthusiasts to modify or even maintain their vehicles. However, the war had an unintended positive impact on the industry. Many young servicemen received extensive training in welding, machining, and fabrication—skills that would later prove invaluable in car customization. Exposure to European sports cars and racing culture further influenced their tastes and ideas, introducing new design concepts that would shape the post-war era.

When the war ended, a booming economy provided returning veterans with disposable income, allowing them to invest in automobiles and modifications. This combination of technical expertise, fresh inspiration, and financial means led to a resurgence in car culture, laying the groundwork for the explosive growth of the custom car scene in the late 1940s and beyond.

A 1949 article, published in The Baltimore Sun, Sun, Apr 17, 1949, highlighted this very transformation in Maryland, where returning servicemen with wartime mechanical training began modifying old cars with homemade speed equipment and custom bodywork. These young men, often working out of garages and basements, applied aviation-inspired techniques and hand-fabricated parts to create what the article called “mechanical works of art.”[5]

Many of these early customizers on the East Coast were heavily inspired by West Coast trends and referred to their creations as “California Jobs” or “California Cars.” These terms reflected the influence of Southern California’s custom car culture, known for sleek styling, chopped tops, and shaved trim. Builds like Ray Giovannoni's 1936 Ford roadster, which received national attention through an article in Hot Rod Magazine, helped cement Maryland’s role in spreading this West Coast-inspired style across the country.[5]

The Post-War Boom and the Lead Sled Era

By the end of the 1940s, the custom car scene was experiencing unprecedented growth. The return of automobile production in 1946 meant newer cars were available for modification. By 1950, the supply was catching up with demand, and prices quickly began to fall. According to Albert Drake, a complete Model A could be had for as little as $5-20 in the late 1940s, "although the average price was somewhere around $75."[6]

The Barris Brothers, the Ayala Brothers, and Valley Custom Shop rose to prominence in the late 1940s, each bringing their own unique style to the movement. Meanwhile, the first car shows and automotive magazines dedicated to customs began appearing, solidifying the genre’s place in American car culture.

Custom Cars of the Early 1950s

According to Portland, Oregon hot rodder, historian and author Albert Drake, a revolution occurred in terms of styling and customizing in the late 1940s and the early 1950s. "Every Detroit car had outgrown what was a pre-war body shape, and the new cars were longer, lower, sleeker. Therefore, many people wanted to make their older cars look more modern, or at least a bit nicer." In 1982 Drake wrote an excerpt about the roots of hot rodding where he pointed out that; "Today we look back at pre-1949 cars with a wistful eye but at the time they seemed drab; high and boxy, with plain interiors, and painted a few standard colors (usually black, dark blue, or grey). It didn't, however, take much to make them more interesting: lowering blocks or shackles, fender skirts, dual exhausts with chrome 'echo cans,' deluxe seat covers and a metallic paint job would cause the guy beside you at the light to sit up and take notice."[7]

Customizing vs Restyling

In 1951, Trend Book 101 Custom Cars was published by Trend, Inc as a result of the growing interest in customized cars. The introduction in the book stated early that restyling and customizing are two things that, like the arts, are better left for the masters. The book defined a custom job as a job that had been custom-built, from the ground up as it were and to order. A restyled job was defined as a stock auto that had been altered somewhat from the original design. Therefore, if you were going to customize a car you would practically start from scratch ending up with a hand-built, totally different creation. If you were to restyle a car, you would change the outside appearance, without evolving a drastically-modified car. The terms were often misused, and in order to explain where the restyled car leaves off and a custom job begins, the following definition was explained in the book: "A restyled car can include any or all of the following modifications without actually being a custom job: a bull-nose, a deck job, fadeaways, a new grille, and/or new bumpers. When it gets to chopped tops and channeling, the car would more properly be termed a custom job." With these two terms defined, the purpose of the book was to show readers the latest trends of customized and restyled cars from coast to coast.[8]

West Coast Restyling of the Early 1950s

Common and favored restyling-features on many West Coast custom jobs in the early 1950s included body modifications such as nosing and decking, license plate set on bumper, tail lights set in bumper guards, dual spotlights and fender skirts.

Deck Out

In the early 1950s, "Deck Out" was a term for restyling a car by adding extra ornamentation such as metal sun visors, chrome exhaust stacks, port holes, extra lights forward and aft, fender flaps, extra radio aerials, bumper guards and more accessories you could buy from your local accessory shop. In the other end were motorists that believed in restyling by smoothing off their cars. This process span from simple modifications such as removal of ornamentation, dechroming and sealing of the car to give a port less, louver-less, one-piece look to chopping the top or channeling the body over the frame.[8]

The Golden Era of the 1950s

During the 1950s, the custom car movement gained momentum, with magazines like Rod & Custom and Car Craft showcasing the innovative work of customizers.[9] The era also saw the rise of hot rods and drag racing, further cementing the custom car culture.

Lowrider and Kustom Kulture of the 1960s and the 1970s

The 1960s and 1970s witnessed the rise of new automotive subcultures, such as lowriders and Kustom Kulture. Lowriders originated in the Chicano community in Southern California, where cars were modified with hydraulic suspension systems for a distinctive "low and slow" look.[10] Meanwhile, Kustom Kulture emerged from a fusion of custom cars, hot rods, and motorcycle influences, with artists like Ed "Big Daddy" Roth and Von Dutch creating unique artwork and pinstriping designs.[11]

Modern Custom Cars

The custom car culture has continued to evolve, incorporating new styles and techniques. The new millennium saw a resurgence of interest in classic customs and hot rods.

Custom Cars of the 1940s

Alex Xydias' 1934 Ford Cabriolet

Bruce Brown's 1936 Ford

Frank Sandoval's 1936 Ford 3-Window Coupe

George Barris' 1936 Ford 3-Window Coupe

Jack Calori's 1936 Ford 3-Window Coupe

Leland Davis' 1936 Ford

Ray Giovannoni's 1936 Ford Roadster

Red Swanson's 1936 Ford Convertible

Robert Fulton's 1936 Ford Sedan Convertible

Tommy Jamieson's 1936 Ford 5-Window Coupe

Vern Simon's 1936 Ford Roadster

Leroy Semas' 1937 Chevrolet Coupe

Neil Emory's 1937 Dodge Convertible

Al Twitchell's 1937 Ford Sedan

Richard Emert's 1937 Ford Convertible

Richard Meade's 1938 Buick Convertible

John Sal Cocciola's 1938 Chevrolet Convertible

George Bistagne's 1938 Ford DeLuxe Convertible Sedan

Harold Johnson's 1938 Ford Tudor

Joe Stone's 1938 Ford Convertible Sedan

Norm Milne's 1938 Ford Convertible Sedan

Arthur Lellis' 1939 Ford Convertible

C. E. Johnson's 1939 Ford

Dick Bair's 1939 Ford Convertible Sedan

Emil Dietrich's 1939 Ford Convertible

G. L. Harlander's 1939 Ford V-8 Convertible Sedan

Harry O. Lutz' 1939 Ford Convertible

Harry Keiichi Nishiyama's 1939 Ford Convertible

Jack Ruynan's 1939 Ford Convertible

Jerry Moffatt's 1939 Ford Convertible

Kenny Controtto's 1939 Ford Convertible

Mel Falconer's 1939 Ford

Mickey Chiachi's 1939 Ford

Bill Henderson's 1939 Mercury Convertible

Bill Spurgeon's 1939 Mercury Coupe

Jim Kierstead's 1939 Mercury Coupe

Bob Creasman's 1940 Ford Coupe

Fred Cain's 1940 Ford Coupe

Gene Garret's 1940 Ford

Johnny Williams' 1940 Ford Coupe

Ralph Jilek's 1940 Ford Convertible

Al Andril's 1940 Mercury Coupe

Butler Rugard's 1940 Mercury

Dick Owens' 1940 Mercury Convertible

Harold Ohanesian's 1940 Mercury Convertible Sedan

Jimmy Summers' 1940 Mercury Convertible

Johnny Zaro's 1940 Mercury Coupe

Maximilian King's 1940 Mercury Convertible

Eldon Gibson's 1940 Oldsmobile

Al Twitchell's 1940 Plymouth Four Door

Bill Hines' 1941 Buick Convertible

Frank Kurtis' 1941 Buick - The Kurtis Buick Special

George Barris' 1941 Buick Convertible

Pierre Paul's 1941 Buick Special

Al Lauer's 1941 Cadillac Convertible

Dick Carter's 1941 Ford Convertible

George Janich's 1941 Ford Business Coupe

Jesse Lopez' 1941 Ford Club Coupe

John Vara's 1941 Ford Convertible

Charles Kemp's 1941 Plymouth Convertible

Dean Batchelor's 1941 Pontiac

Marvin Lee's 1942 Chevrolet Fleetline

George Shugart's 1946 Chevrolet Convertible

Raymond Jones' 1947 Studebaker Convertible

Vincent E. Gardner's 1947 Studebaker Sportster

Benny Furtado's 1948 Ford Convertible

Albrecht Goertz's 1948 Studebaker Business Coupe

Marcia Campbell's 1949 Chevrolet Convertible

Custom Trucks of the 1940s

Charlie Grantham's 1935 Ford Pick Up

Sport Customs of the 1940s

Norman Timbs' Buick Special

The Rotzell 46

Robert McClure's Custom

George McLaughlin's Roadster

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Sondre Kvipt

- ↑ Kurtis-Kraft: Masterworks of Speed and Style

- ↑ Motor Life May 1955

- ↑ Rod & Custom August 1990

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 The Baltimore Sun, Sun, Apr 17, 1949

- ↑ Reflections in a Spinner Hubcap

- ↑ Reflections in a Spinner Hubcap

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Trend Book 101 Custom Cars

- ↑ Batchelor, Dean. "The Birth of Hot Rodding." In The American Hot Rod, Motorbooks, 2002.

- ↑ Reighard, Heidi. "Lowrider: A History of Custom Cars and the Lowrider Movement." Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 39, no. 4, Aug. 2006, pp. 585-601.

- ↑ Witzel, Michael Karl. "Kustom Kulture: Von Dutch, Ed 'Big Daddy' Roth, Robert Williams and Others." In The American Custom Car, Motorbooks, 2001.

Did you enjoy this article?

Kustomrama is an encyclopedia dedicated to preserve, share and protect traditional hot rod and custom car history from all over the world.

- Help us keep history alive. For as little as 2.99 USD a month you can become a monthly supporter. Click here to learn more.

- Subscribe to our free newsletter and receive regular updates and stories from Kustomrama.

- Do you know someone who would enjoy this article? Click here to forward it.

Can you help us make this article better?

Please get in touch with us at mail@kustomrama.com if you have additional information or photos to share about Custom Cars.

This article was made possible by:

SunTec Auto Glass - Auto Glass Services on Vintage and Classic Cars

Finding a replacement windshield, back or side glass can be a difficult task when restoring your vintage or custom classic car. It doesn't have to be though now with auto glass specialist companies like www.suntecautoglass.com. They can source OEM or OEM-equivalent glass for older makes/models; which will ensure a proper fit every time. Check them out for more details!

Do you want to see your company here? Click here for more info about how you can advertise your business on Kustomrama.