1930s

The 1930s marked the beginning of hot rodding and custom car culture in America. Despite the Great Depression, mechanically minded young men began modifying old Fords—especially Model Ts and Model As, for better speed and performance. Dry lake beds like Muroc and Rosamond in Southern California became popular testing grounds. Early customizers such as Harry Westergard in Northern California began reshaping body lines for a more elegant, personalized look, laying the groundwork for what would become traditional customizing. The 1930s were a time of experimentation, innovation, and the birth of a movement that would flourish in the decades to come.

Contents

- 1 The Birth of the Custom Car Movement

- 2 Design Trends of the 1930s: A Decade of Style

- 3 The Pioneering Spirits: Frank Kurtis

- 4 George DuVall: A Visionary in Custom Design

- 5 Emerging Trends and Custom Techniques of the 1930s

- 6 Dry Lakes Racing

- 7 Hot Rods of the 1930s

- 8 Custom Cars of the 1930s

- 9 Sport Customs of the 1930s

- 10 Nordic Special Racers of the 1930s

- 11 Speed Shops of the 1930s

- 12 Custom Body Shops of the 1930s

- 13 Custom Car Builders of the 1930s

- 14 Hot Rod and Custom Car Clubs of the 1930s

- 15 Dry Lake Meets of the 1930s

- 16 References

The Birth of the Custom Car Movement

For over 100 years, people have been customizing cars to make them stand out and show off their personal style. In the early days, the term "Custom Car" referred to luxury vehicles commissioned by the wealthy and influential. These cars, often created by renowned coachbuilders like Brunn or Dietrich, were built from scratch or heavily modified on high-end chassis to reflect the owner's unique tastes and needs. They were symbols of status, combining bespoke craftsmanship with cutting-edge engineering.[1]

At the same time, a more grassroots movement began to emerge. Some people started taking regular, mass-produced cars and making modifications to improve their looks or performance. These changes, often done on a budget, became known as "Restyled Jobs." Unlike the high-end "Custom Cars," restyling was more accessible and marked the beginning of a do-it-yourself approach that would shape car culture for generations.[1]

Design Trends of the 1930s: A Decade of Style

The 1930s were a groundbreaking era for car design, where creativity flourished despite the challenges of the Great Depression. Automobiles became more than just functional machines—they were symbols of progress, luxury, and individuality. Several design movements defined the decade, each contributing to the evolution of custom cars.[1]

Streamlining was the most influential style of the 1930s, inspired by advancements in aerodynamics and the sleek forms of airplanes like the Douglas DC-3. This trend emphasized smooth, flowing lines that reduced drag and gave cars a futuristic appearance. Cars like the Chrysler Airflow embodied the philosophy of Streamlining, and customizers began adapting it by lowering rooflines, smoothing body panels, and eliminating bulky details.[2]

Art Deco brought an elegant, glamorous aesthetic to automotive design. Known for its bold geometric shapes and intricate detailing, this style was showcased in vehicles like the Cord 810. Custom builders added touches such as flared grilles, decorative trim, and unique hood ornaments to create rolling works of art that reflected the sophistication of the era.[1]

Amid these forward-looking designs, the Neo-Classical Revival offered a nod to the past. Luxury brands like Packard and Duesenberg produced cars with long hoods, upright grilles, and ornate detailing, blending old-world charm with modern engineering. These vehicles appealed to those who valued tradition and timeless elegance, often showcased at exclusive events like the Packard Custom Car Salon.[1]

Functionalism, a simpler style focused on practicality, emerged for those seeking affordable and reliable vehicles. Cars like the 1937 Ford Standard reflected this approach, with clean lines and minimal ornamentation. Grassroots customizers embraced this style, making subtle modifications to improve performance and aesthetics without extravagant embellishments.[1]

Together, these styles defined the 1930s, shaping the custom car movement and setting the stage for the explosion of creativity in the decades to come. Whether streamlined, glamorous, traditional, or practical, these designs reflected the era’s spirit of innovation and resilience.[1]

The Pioneering Spirits: Frank Kurtis

For many teenagers during the Great Depression, owning a car was a rare luxury. Those fortunate enough to have one often held onto it, adapting and upgrading it rather than trading it for newer models. Frank Kurtis, an early custom car pioneer, epitomized this resourcefulness and creativity. His journey began in 1925, at the age of 17, when he joined Don Lee Body Works as an apprentice. Don Lee’s shop, one of the finest custom coachbuilders on the West Coast, was steeped in a culture of artistry and precision. Kurtis quickly proved himself, mastering sheet metalwork and eventually becoming the manager of Don Lee's Los Angeles Coachworks.[3]

During his time at Don Lee, Kurtis briefly worked alongside Harley Earl, the legendary designer who would later shape automotive styling at General Motors. The experience left a lasting impression on Kurtis, who carried forward Don Lee’s ethos of high-quality craftsmanship and bold design into his own work.[4]

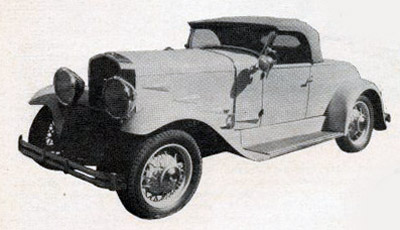

After hours, Kurtis spent his free time crafting sporty, open-top roadsters using salvaged parts from various cars. His designs often featured boattail bodies, inspired by the elegance of expensive coachbuilt automobiles. In 1928, Kurtis purchased a new 1928 Ford Model A Roadster and began experimenting with its design. By incorporating 1930 Ford fenders, a lengthened hood, a custom radiator shell, and Cadillac headlights, he transformed the car into a sleek, futuristic custom. It was a clean, unified design that stood apart from earlier, more ornamental styles. His modifications marked the emergence of a new trend in custom cars, emphasizing smooth lines and cohesive styling. Kurtis didn’t stop there. In 1931, he restyled a 1931 Ford Model A Roadster with a custom grille shell that closely resembled the one later used on 1935 Fords. Many believe his work influenced the design of the 1935 Ford grille itself, a testament to his forward-thinking approach.[3]

In 1932, Kurtis left Don Lee to open his own garage behind his home, but financial struggles led him to return to Don Lee Motors in 1935. Upon his return, Kurtis took on several high-profile custom projects, including two streamlined equipment trucks for Lee’s Columbia Broadcasting radio stations in Los Angeles and San Francisco. These trucks, built on Cadillac V-16 chassis, featured bold Art Deco designs and served as promotional tools for the stations. Another notable build was a 1934 LaSalle Boattail Speedster commissioned by Willet Brown, the son of Don Lee’s manager. Starting with a badly damaged LaSalle coupe, Kurtis reconstructed the car into a stunning Boattail Speedster, completed in 1935 or 1936. The car exemplified Kurtis’s ability to turn discarded vehicles into breathtaking works of art, blending functionality with an eye for striking design.[4]

Kurtis’s innovative approach to customization, rooted in his time at Don Lee and his own hands-on experimentation, set a standard for future customizers. His work reflected a fusion of craftsmanship, creativity, and practicality, laying the foundation for the custom car movement that would flourish in the decades to come.[1]

George DuVall: A Visionary in Custom Design

George DuVall, another one of the early pioneers of the custom car scene, combined technical skill with an eye for bold design to leave a lasting mark on the custom car movement. A 1931 graduate of Hollywood High School, DuVall enrolled at UCLA to study mechanical engineering, but his passion for cars quickly steered his path in a different direction.[5]

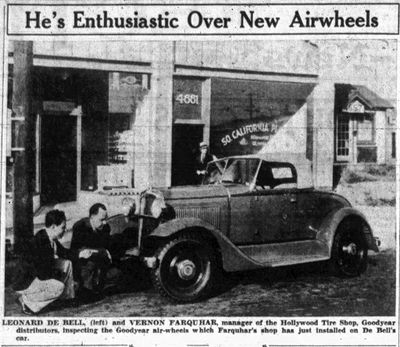

While in school, DuVall took a part-time job at Southern California Plating Company after seeing their delivery truck with Los Angeles's first set of Goodyear balloon tires. Initially hired for odd jobs, DuVall’s talent for car customization soon caught the attention of the company’s owner, Leonard DeBell. Influenced by Harley Earl’s innovative designs, DuVall began creating custom grilles and bumpers, often for Depression-era Fords. His work offered customers an affordable way to achieve a Cadillac-style luxury, with everything finished in chrome—a signature of the time.[5]

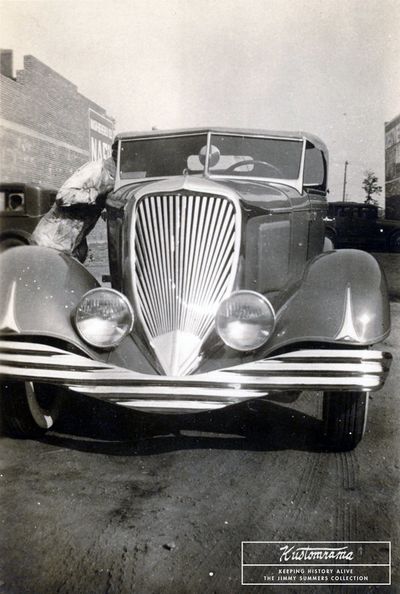

In 1933, DuVall left UCLA to work full-time at Southern California Plating, where he took on increasingly creative projects. One of his early successes was the company’s fleet of customized delivery trucks, which were used to promote the business. His most famous creation was the Southern California Plating Company's 1935 Ford Phaeton delivery truck, completed in 1936. The truck featured the first-ever DuVall-Windshield, a sleek, V-shaped, five-piece bronze casting that became an iconic design element in the hot rod and custom car world. It wasn’t long before requests for DuVall windshields poured in, and DuVall oversaw both their design and production.[5]

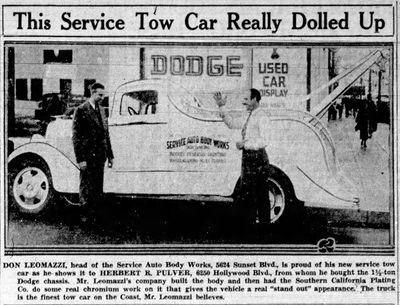

DuVall’s personal cars showcased his innovative style. His 1929 Ford Model A Roadster, restyled by Don Leomazzi’s Service Auto Body Works, featured full-skirted fenders, solid hood sides, a 1932 Plymouth grille shell, ripple discs over Kelsey wire wheels, and custom bumpers and a V-windshield crafted by DuVall himself.[5]

George DuVall’s contributions to the custom car scene bridged the gap between functionality and artistry, helping to define the aesthetic of early custom cars. His iconic designs, particularly the DuVall windshield, remain celebrated hallmarks of the movement to this day.

Emerging Trends and Custom Techniques of the 1930s

Custom car modifications of the 1930s were rooted in ingenuity and craftsmanship. The smaller diameter, larger tired wheels, which would fit earlier models, were also sought after by early customizers. Lowering the cars and esoteric considerations such as white leather upholstery and headlining became more common. With the emergence of the flared fender came the fender skirts, followed immediately by the fender skirt lock. The "nosed-over hood", "planed deck" and interior release latches came on about the same time and grew in popularity.[3] Metallic enamels, introduced in 1935, added an extra layer of sophistication. According to George Barris, a future giant in the custom car world, maroon was the most popular color, followed by green and blue, creating bold and elegant statements on the road.[6]

As production cars put the radiator filler cap out of sight, everyone wanted an alligator-style hood that led to a solid front and dropped grille. By the mid-1930s, customized cars had started to pop up all over the United States. As the 1930s drew to an end, the move toward enclosure of all parts and other customizing methods were aimed at smoothing, cleaning, and sharpening the stock lines. Work was often done on 1937 through 1939 Fords and Chevrolets. In the early days of customizing, it was mostly open cars that had been preferred. By the end of the 1930s, sedans and coupes were also more often customized, especially club coupes.[3]

Following the emerging streamlining trend, early customizers such as Jimmy Summers and Harry Westergard would lower the rooflines, smoothing contours, stretching and lowering the body on Fords and Mercurys into shapes closer to a teardrop. The cars were restyled to resemble coach-built European and American cars, sharing shapes with streamlined locomotives such as the Commodore Vanderbilt.[2]

As chopped hot rods and customs became more regular on the streets of Southern California, the usual yardstick for determining how much window area to leave was a giant malt or soda glass. If you could get a barely full malt glass through the window while parked at a drive-in, the top had been chopped right. With the new lowered steel tops came new sensitivity to interiors, and upholstery shops started to make good money from stitching up splashily colored materials.[3] In 1935, the first non-folding padded, smooth-lined "Carson Top" was built by Carson Top Shop employee Glen Houser. The top was built for a 1930 Ford Model A Convertible. The design's popularity quickly grew, and the Carson Top Shop became very busy making Carson Tops for countless customs and hot rods. The Carson Tops were so nicely done inside and out that the renovation of the seats and trim became the primary step in many expressions of individuality.[3]

According to Motor Life May 1955's story on the birth of customizing, one of the most popular custom touches in the 1930s was the inset license plate. This trick was supposedly first performed by Frank Kurtis on an Airflow DeSoto in 1936, and the story claims that this feature, more than any other feature, marked the "California Car" back then.[3]

By the late 1930s, customized or restyled cars could be spotted anywhere in Southern California. Lowered, de-chromed, with smooth hood and deck, set-in plates and maybe a chopped top. The lines of a custom car created an impression of speed. It was the look of the future.[3] The trend had also reached the east coast by now, and Bob Hart's 1932 Ford Roadster, which was built between 1938 and 1939 is one of the first known east coast customs. It looks like Bob got much of his inspiration from cars such as Southern California Plating's 1931 Ford Model A Delivery Truck.

The 1930s laid the groundwork for the custom car movement, blending technological innovation with artistic expression. Despite economic hardship, enthusiasts transformed their cars into personal statements of style and ingenuity. As the decade ended, the custom car scene had established a distinct identity, setting the stage for the explosive growth of customization in the decades to come.

Dry Lakes Racing

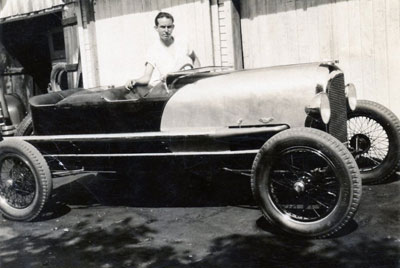

Harry Reinhert began attending dry lake races in 1931. According to him, the first meets were small. "There were anywhere from fifteen to twenty-five cars, thirty at the most, out there - a few motorcyclists too." Dry lake activities for amateurs were spontaneous and informal. Sometimes you could meet a handful of gearheads to talk to and race against, other times you might not find anyone there. If you found someone to race, you raced without rules.In 1931 one of the first known organized amateur speed trials was held at Muroc. It was sponsored by Gilmore Oil Company of Los Angeles. The driving force behind the event was George Wight, the owner of Bell Auto Parts. George realized that something had to be done to coordinate the haphazard dry lakes meets. He got Gilmore Oil Company to sponsor the speed trials if the hot rodders could come to an agreement regarding rules and regulations. Early in 1931 Wight sent letters to rodders in the area inviting them to an organizational meeting to be held in East Los Angeles. The rules that were made were fairly simple in the beginning. In the interest of fairness, classes were established according to engine type: Model T flatheads, Model T Rajos, Model T Frontenacs and Chevrolets, Model A flatheads, and Model A overhead valve conversions. Supercharged cars were not allowed to compete. The first organized meet was held March 25, and the second was held April 19, 1931. The speed trials were open to all cars within the designated class. A pace car would start up a dozen racers at a time. At around 50 mph the pace car would drop back and the racers would continue to accelerate to the finish line. No "wildcat warmups" were allowed, and any car that jumped the start would be given a penalty of a hundred foot handicap when the race was restarted. The need for safety was recognized, and cars returning from a speed run were limited to 40 mph. The cars ran as a group, and the two fastest cars from each class were eligible to run in the open competition from which a single winner would emerge. No records exist of the two Gilmore sponsored runs held in 1931, but it has been documented that Ike Trone won the Gilmore trophy for first place in the Main Event at the second met on April 19th. Ike ran a fenderless, stock bodies 1929 Ford Model A roadster with a Riley head.[7]

Before the 1931 season ended, the Muroc Racing Association had been formed, complete with officers and a race program. It collected a one dollar entry fee which was used to meet the expenses. The same year the Purdy Brothers developed an electrical timer to clock the cars speeds. These two helped formalize the meets radically.[7]

The quest for speed in the 1930s involved automobile companies as well as individuals. During the summer of 1932 Auburn made several speed runs at Muroc. A stock V-12 Auburn speedster covered the flying mile at 100 mph, and posted an average speed of 88.95 mph for a 500 mile run to set a new track record. In 1932 Ab Jenkins removed the fenders and windshield from a Pierce-Arrow V-12 roadster, and without factory sanction, drove around the ten mile diameter track at the Bonneville Salt Flats for 24 hours. He averaged at 112.93 mph, setting a new record, but it remained unofficial because of a dispute between driver, manufacturer and the AAA board. In 1933, Jenkins returned to the salt as a special consultant on high speed performance for Pierce Arrow. He encouraged the factory to bore the V-12 to 3 1/2", giving it a displacement of 462 ci. He bought a new V-12 convertible coupe that was specially geared for top end. Driving it around the same ten mile track for 24 hours, Jenkins turned an average speed of 177.77 mph. This meet was sanctioned by AAA, and it recorded that he broke 66 American and 14 world stock car records. Jenkins, who later became mayor of Salt Lake City, wanted to promote the salt as a speed course superior to Daytona Beach, and used his own money to make a three reel film of his 1932-1933 speed runs. Jenkins sent copies to Sir Malcolm Campbell and Reid Railton, who were known as the British speed kings. In 1934 the British invaded the salt. Record attempts were made by Campbell, Railton, John Cobb and Captain G.E.T. Eyston. When Cobb set a world record of 352 mph, Eyston drove 357 mph hours later and broke it. Suddenly speed was in the air, and Bonneville had become the center of straight line record attempts.[7]

In 1934 Ab Jenkins returned to the salt with a creation built on Pierce-Arrow V-12 chassis. The chassis was fit with a streamlined racing body and a large tail. The big British cars achieved speed through brute horsepower, using aircraft engines. Jenkins hopped up the V-12 by adding a homemade six-carburetor intake manifold. The heads were milled to increase compression. These modifications upped his horsepowers from 175 to 235, raising his average speed to 127.29 mpg. In 1935 he built a special supercharged Duesenberg, and in 1936 he built the famed Mormon Meteor. With the Mormon Meteor Jenkins brought back all the world record between 50 miles and 48 hours inclusive to the U.S. His speed for 24 hours average was 153.82 mph, and for 48 hours 148.64 mph. Jenkins continues to run the Mormon Meteor, and during the next few years he set more than 25 new records.[7]

Hot Rods of the 1930s

The Glen Smith Special

Fredric "Freddy" G. Bearcroft's Ford Model T Roadster

Jack Engle's Ford Model T Roadster

Julian Doty's 1923 Ford Model T Roadster

Pete Clark's 1925 Ford Model T Roadster

Jim Woods' Ford Model T Roadster

Al Hawkins' 1927 Chevrolet Touring

Glen Wall's 1928 Chevrolet Coupe

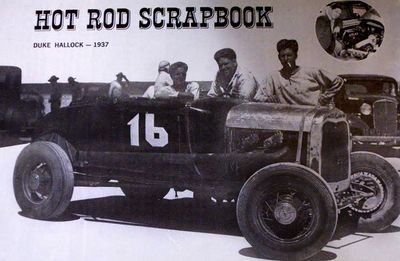

Duke Hallock's 1928 Ford Model A Roadster

Ike Trone's 1929 Ford Model A Roadster

Karl Orr's 1929 Ford Model A Roadster

Arvid Johansen's 1930 Ford Model A Roadster

Harry Reinhart's 1930 Ford Model A Roadster

Julian Doty's 1931 Ford Model A Roadster

Robert Stack's 1931 Ford Model A Roadster

Bob Minor's 1932 Ford Roadster

Bob Westbrook's 1932 Ford Roadster

Dick Noble's 1932 Ford Roadster

Bob Minor's 1934 Ford Tudor

Custom Cars of the 1930s

Frank Kurtis' 1928 Ford Model A Roadster

George DuVall's 1929 Ford Model A Roadster

Frank Kurtis' 1931 Ford Model A Roadster

Southern California Plating's 1931 Ford Model A Delivery Truck

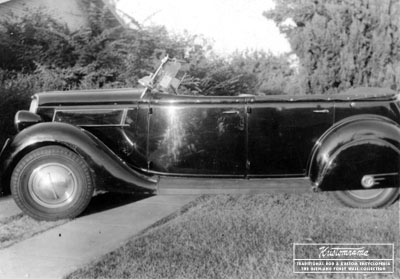

Bob Hart's 1932 Ford Roadster

Glen Wall's 1935 Ford Phaeton

Southern California Plating's 1935 Ford Phaeton

Tommy the Greek's 1936 Ford Phaeton

Rudy Makela's 1936 Pontiac

1937 Kurtis Tommy Lee Special

The Phantom Corsair

Marquis Hachisuka's 1937 Lincoln Zephyr

The Don Morris Special

Bill Hughes' Roadster

Link Paola's 1940 Ford

Albrecht Goertz' 1940 Mercury Coupe

Sport Customs of the 1930s

The Topper Sport Custom

The Eugene Von Arx Special

Nordic Special Racers of the 1930s

Greger Strøm Special No. 1

Greger Strøm Special No. 2

Speed Shops of the 1930s

Custom Body Shops of the 1930s

Indianapolis Power Hammer Works Inc

Jimmy Summers Custom Automobile Body Shop

Link's Custom Shop

Custom Car Builders of the 1930s

Frank Kurtis

George DuVall

Jimmy Summers

Link Paola

Hot Rod and Custom Car Clubs of the 1930s

Albata

Glendale Sidewinders

Gophers

Hollywood Throttlers

Hot Iron

Kings Men

Mercuries

Night Flyers

Outriders

Pacemakers

Road Runners

Santa Monica Low Flyers

Throttle Throbbers

Dry Lake Meets of the 1930s

Muroc March 25, 1931

Muroc April 19, 1931

Muroc Roadster Races June 14, 1931

Muroc Roadster Races May 15, 1938

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Sondre Kvipt

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cool Cars, High Art. The Rise of Kustom Kulture

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Motor Life May 1955

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Automobile Quarterly:Vol-39 #1

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Rod & Custom August 1990

- ↑ Barris Kustom Techniques of the 50's Volume 4

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Flat Out

Did you enjoy this article?

Kustomrama is an encyclopedia dedicated to preserve, share and protect traditional hot rod and custom car history from all over the world.

- Help us keep history alive. For as little as 2.99 USD a month you can become a monthly supporter. Click here to learn more.

- Subscribe to our free newsletter and receive regular updates and stories from Kustomrama.

- Do you know someone who would enjoy this article? Click here to forward it.

Can you help us make this article better?

Please get in touch with us at mail@kustomrama.com if you have additional information or photos to share about 1930s.

This article was made possible by:

SunTec Auto Glass - Auto Glass Services on Vintage and Classic Cars

Finding a replacement windshield, back or side glass can be a difficult task when restoring your vintage or custom classic car. It doesn't have to be though now with auto glass specialist companies like www.suntecautoglass.com. They can source OEM or OEM-equivalent glass for older makes/models; which will ensure a proper fit every time. Check them out for more details!

Do you want to see your company here? Click here for more info about how you can advertise your business on Kustomrama.