Ralph Lysell

Rolf Åke Nystedt (1907 - 1987), later known as Ralph Lysell, was a Swedish industrial designer, engineer, and adventurer. Born in Stockholm, Sweden, Lysell led an extraordinary life, marked by innovation, ambition, and a series of remarkable career shifts across multiple countries. He played a pioneering role in industrial design, worked for major European automakers, and even attempted to build one of Norway’s first sports cars.[1]

Contents

Early Life and Move to the United States

Born in 1907 in Stockholm, Sweden, Rolf Åke experienced a difficult childhood after his mother moved to the United States when he was seven years old. Longing to reunite with her, he emigrated at the age of 16. Upon arrival, he encountered hostility from his stepfather and was forced to fend for himself. To better integrate into American society, he changed his name to Ralph Lysell, adopting his mother’s maiden name, and lied about his age.[1]

At just 17, Ralph married for the first time, an early start to what would become a string of seven marriages. Driven by a relentless ambition to excel in everything he pursued, he took pride in his physical strength and distinctive full beard, which he considered his signature feature. According to his sixth wife, he even slept on his back to avoid disturbing it.[1]

Lysell was determined to succeed. While taking night classes at Columbia University, he trained as a heavyweight boxer in underground gyms, aiming for a professional career. A polyglot, he mastered seven languages fluently, and at some point during the 1920s or 1930s, he obtained a pilot’s license. His adventurous spirit also led him to South America in the 1930s, where he was involved in a film project.[2]

The American Dream and the Lost Automobile

Ralph Lysell’s technical education at Columbia University fueled his passion for innovation, leading him to design a streamlined automobile in the 1930s that was far ahead of its time. This revolutionary vehicle featured a rear-mounted engine, a gearless transmission, a stamped one-piece frame, and doors that slid along the bodysides. Its teardrop-shaped body was designed for maximum aerodynamics, offering unobstructed visibility from all angles, features that made it stand out in an era dominated by more traditional automotive designs. According to an article in Daily News, Sun, Nov 04, 1934, Page 52, the car was engineered to run on either crude oil or gasoline, with a 50-horsepower engine capable of 40 miles per gallon on crude oil and 28 miles per gallon on gasoline. Three versions were planned, with 40, 80, and 160-horsepower options and wheelbases ranging from 90 to 120 inches. Lysell reported from his retreat “somewhere on Long Island” that the first prototype would be completed within two weeks.[3]

Despite its promising design, the car never made it into production, and the reasons for its failure remain unclear. Conflicting reports attempt to explain its fate. One version, published in Teknik För Alla Nr 34. 21 aug 1942., claims that the American auto industry forced Lysell out, fearing his modern design would pose a threat to established manufacturers. According to this account, he was paid off and made to sign a contract prohibiting him from working in the American automotive or aviation industries for five years.[4] Another explanation, detailed in the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten in 1951, suggests that a flood destroyed the factory where the car was being built, halting production entirely. A third theory holds that Lysell ran out of funds, unable to secure enough backing to bring the vehicle to market. Some even speculate that angry investors forced him to flee the country.[2]

Whatever the true reason, Lysell left the United States and returned to Europe, abandoning his dream of revolutionizing the automobile industry.[2]

The Rise and Fall of AB Industriell Formgivning

Back in Europe, Lysell worked as a consulting engineer in Germany, collaborating with Mercedes-Benz, Adler, and BMW.[4] He also served as a test driver for Mercedes-Benz. In 1939, while on a promotional tour in Stockholm, Sweden, World War II broke out, prompting him to stay.[5]

Lysell was soon hired as an industrial designer at L.M. Ericsson, where he played a pivotal role in early designs for the Ericofon, one of the most iconic telephone designs in history. In 1941, he and Knut Hugo Blomberg filed a patent for an early Ericofon prototype. However, Lysell felt creatively stifled at Ericsson, describing himself as a “trapped lion.”[5]

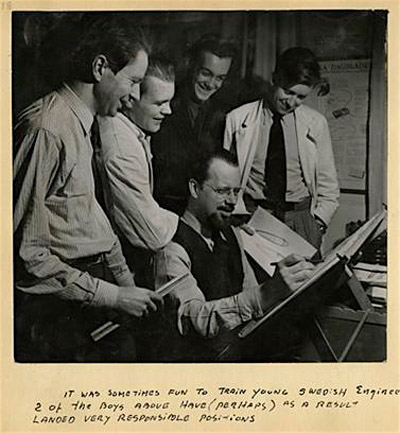

By 1945, he had established his own design firm, AB Industriell Formgivning at Katarinavägen 22 in Stockholm, backed by advertising agency Günther & Bäck. His work, inspired by aviation and space design, attracted major clients like Volvo, AGA, Electrolux, Kockums, Sandvik, and Svenska Amerikalinjen. One of his notable contributions to Volvo was the “Takgök” for the PV models.[1]

Despite his artistic brilliance, Lysell struggled with business management. By 1947, his firm employed eight people, but financial difficulties mounted. He began arriving late to work—or disappearing entirely. The company lost its contract with Ericsson, and by winter, AB Industriell Formgivning went bankrupt.[1]

Desperate for a new opportunity, Lysell and former employee Erik Olsson developed a machine for manufacturing wooden clothespins, securing funding from optimistic farmers in Torsby, Sweden. The venture collapsed financially, leaving the investors furious. Facing legal threats, Lysell and Olsson fled to Paris, France.[1]

The Rally Sports Car

After a few years in Paris, Lysell relocated to Norway in 1949, where he married a Norwegian woman named Carlmeyer and had a son, Gösta.[2]

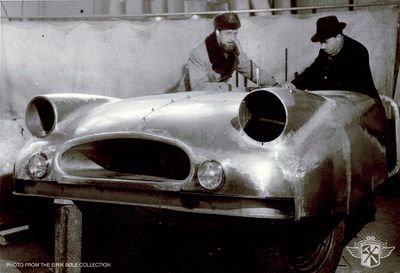

In Norway, Lysell set out to build a futuristic sports car, the Rally. Designed with an aluminum body and a bubble-top canopy, it was intended to be Norway’s first sports car of the 1950s. His vision extended beyond the Rally, he also had plans for a Norwegian-produced taxi and a truck.[6]

The sole Rally prototype was built at Norwegian Aircraft Industries LTD at Fornebu, Oslo’s main airport. However, the project never progressed beyond this single model. According to a 1953 article in Teknikens Värld, Lysell abandoned his automotive dream to design an aluminum lifeboat called "Svelvik"—intended to be unsinkable.<ref name="tv">

To prove its capabilities, Lysell sailed the Svelvik from Norway to Gothenburg during winter. Battling fierce winds and snow, he endured three days at sea before arriving safely.[1]

Later Years and Legacy

After 11 years in Norway, Lysell returned to Sweden in 1960, settling in Hjo, where he worked as a designer at Hjo Mekaniska Verkstad. He was later seen at Electrolux in Alingsås, inquiring about design work, though he was turned down. According to his son Gösta, he also served as a guest professor at a London university in the 1960s.[1]

A devoted gearhead, Lysell spent the 1960s traveling across Europe in an Austin Healey. In the 1970s, he embarked on a trip to Africa, during which he disappeared for a prolonged period and was reported missing before eventually resurfacing.[1]

In his later years, he retired in Sweden, dedicating much of his time to painting abstract art. Ralph Lysell passed away in 1987.[1]

Ralph Lysell: The Man and the Myth

Lysell’s larger-than-life persona gave rise to numerous myths and rumors. A charismatic and eccentric adventurer, he had a knack for convincing people to believe in his visions—sometimes to their financial detriment.

One unconfirmed rumor suggests that while living in the U.S., Lysell helped Al Capone smuggle alcohol across the Canadian border using small airplanes. Another unverified story claims that in 1942, after leaving L.M. Ericsson, he went to Germany and worked for Hitler’s automobile division.

Despite the embellishments and speculation surrounding his life, Ralph Lysell remains a fascinating figure in industrial design and automotive history, remembered for his unorthodox ideas, relentless ambition, and the bold, futuristic concepts he pursued.

References

Did you enjoy this article?

Kustomrama is an encyclopedia dedicated to preserve, share and protect traditional hot rod and custom car history from all over the world.

- Help us keep history alive. For as little as 2.99 USD a month you can become a monthly supporter. Click here to learn more.

- Subscribe to our free newsletter and receive regular updates and stories from Kustomrama.

- Do you know someone who would enjoy this article? Click here to forward it.

Can you help us make this article better?

Please get in touch with us at mail@kustomrama.com if you have additional information or photos to share about Ralph Lysell.

This article was made possible by:

SunTec Auto Glass - Auto Glass Services on Vintage and Classic Cars

Finding a replacement windshield, back or side glass can be a difficult task when restoring your vintage or custom classic car. It doesn't have to be though now with auto glass specialist companies like www.suntecautoglass.com. They can source OEM or OEM-equivalent glass for older makes/models; which will ensure a proper fit every time. Check them out for more details!

Do you want to see your company here? Click here for more info about how you can advertise your business on Kustomrama.