The 1960 Car Club Murder

On March 28, 1960, a brutal altercation between two rival car clubs, the Townsmen and the Dutchmen of Paramount, unfolded at the Lakewood Moose Lodge Hall on Artesia Street in Long Beach, California. The violence that erupted that night would not only claim the life of 16-year-old Neil Mahan but also leave an indelible mark on the community, sparking legal battles, community outrage, and widespread efforts to prevent further bloodshed.[1]

Contents

- 1 The Night of the Attack

- 2 The Motive Behind the Violence

- 3 Eyewitness Account from Jim Beeson

- 4 Mickey Mefford's Story

- 5 Eddie Padilla’s Son Speaks Out

- 6 Patrick Farrell on the Car Club Scene

- 7 The Investigation and Arrests

- 8 The Vandals' Role and the Threat of Retaliation

- 9 Community Response

- 10 Revelations from the Townsmen's Diary

- 11 The Trial and Sentencing

- 12 The Aftermath and Long-Term Impact on Long Beach

- 13 References

- 14 Sources

The Night of the Attack

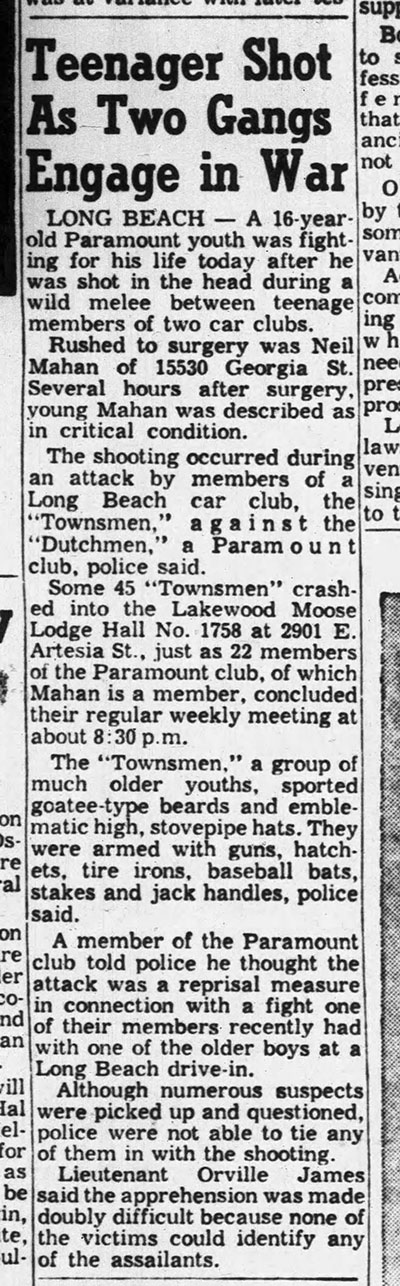

The Townsmen, a car club known for its distinctive dress code of stovepipe hats and goatee-style beards, arrived at the Dutchmen's meeting heavily armed and ready for a fight. Witnesses described the Townsmen carrying guns, baseball bats, wrenches, tire irons, and other weapons. The attack was swift and brutal. Windows and doors of the Moose Lodge were shattered, and the Townsmen mercilessly beat the Dutchmen members they encountered. Amid the chaos, Neil Mahan, a Paramount High School student, sought refuge in the kitchen. As he attempted to hide, a .25-caliber bullet struck him in the head, fired by 21-year-old Eddie Padilla through a window.

Mahan was rushed to Long Beach Community Hospital, where doctors performed emergency surgery. Despite their efforts, he remained in a coma, and the hopes of his recovery dwindled. Five days later, Mahan succumbed to his injuries, leaving his family and the community devastated.

The Motive Behind the Violence

Reports indicated that the “rumble” was in retaliation for the Dutchmen's recent resistance to the Townsmen, who had attempted to move into a Lakewood drive-in restaurant, most likely Hody's, a popular cruising destination. Tensions between the two clubs had been escalating, fueled by disputes over territory and dominance in the local car club scene. This territorial conflict added another layer of complexity to the events that led to the fatal confrontation.

Eyewitness Account from Jim Beeson

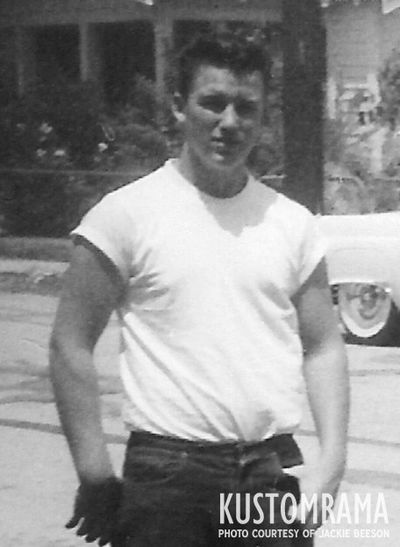

In 2012, Dutchmen member Jim Beeson shared his firsthand experience of that night with Sondre Kvipt of Kustomrama. Jim, who was a member of the Dutchmen of Paramount car club from 1959 to 1960, recalled the terrifying moments when the Townsmen stormed their meeting. At the time, Jim owned a ‘53 Plymouth two-door, which he had lowered, shaved most of the exterior chrome off, added fancy hubcaps, and fitted with a tonneau tarp from the back of the front seat to the package tray.[2]

According to Jim, the explanation that the Townsmen were seeking a "peace meeting" was completely false. "We were just having our meeting, messing around when the Townsmen busted through the door and the windows," he explained. "We were outnumbered by about two to one, but to make it even worse the attackers had various weapons; they came fully prepared. I had never run away from a fair fight in my life, but being no dummy, me and my friends got out of there as fast as we could. The Townsmen members, for the most part, were older guys. We were high school kids. I was 16."[2]

Mickey Mefford's Story

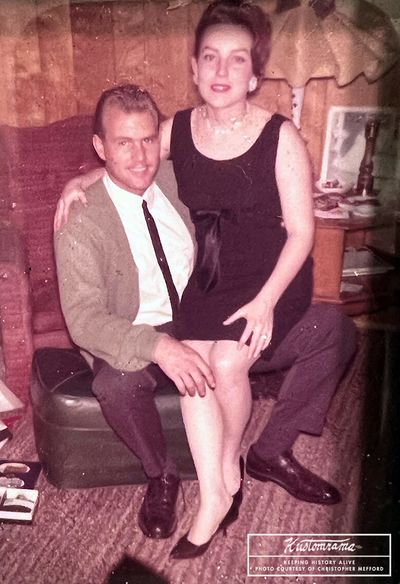

Among the Townsmen caught up in the incident was Mickey Mefford. In June of 2023, his son, Christopher Mefford, told Sondre Kvipt that his father ended up serving a year in LA County jail, "even when he wasn’t the shooter." After serving his sentence, Mickey had to make a difficult choice: join the Armed Services or continue his stay in jail. He chose to enlist in the Air Force, where he became a jet engine mechanic stationed in Okinawa. This turn of events marked a significant shift in Mickey’s life, shaping his future away from the violence that had gripped Long Beach.[3]

Eddie Padilla’s Son Speaks Out

In January of 2021, Eddie William Padilla’s son, Eddie Padilla, shared his reflections with Sondre Kvipt. Eddie Jr. explained that his father had never spoken about the rumble. Padilla Sr. passed away on September 26, 2006, and most of the information Eddie Jr. knows comes from news articles and family members. "My grandmother, his mom, confirmed much of it, and it was told to me through an aunt. Especially as they visited him in the prisons in the 1960s," he said.[4]

Eddie Jr. described his father as a man who loved cars but had lived a hard life. "He grew up in Romana Gardens and was forced into a gang in the 1940s as a kid. Hard life was ingrained in him. He had to join like with the White Fence and El Hoyo Maravilla back then to survive." Padilla Sr. had two brothers who also loved cars, but both died young—one in a car accident on Whittier or Beverly in the 1950s and the other in a drag race that ended tragically when he drove off a cliff. Eddie Jr. emphasized that his father deeply regretted the incident. "It apparently was a stupid attempt of him trying to join the Townsmen in 1960. He just went overboard and didn't think about his actions and how it would end a life. It never sounded intentional, more like a show, and he just didn't count on the consequences."[4]

Patrick Farrell on the Car Club Scene

Patrick Farrell, a member of the Long Beach Cavaliers, provided valuable context about the car club scene in Long Beach at the time. In March of 2021, he told Sondre Kvipt that there were between 20 and 30 car clubs in the area. The Cavaliers, associated with Poly High and the west side, were one of the top clubs, along with the Rebels from the east side connected to Wilson High, and the Jesters from the north side and Jordan High. The Townsmen, centered around Millikan High in Lakewood, emerged in the late 1950s and quickly developed a reputation for breaking the unwritten rules of car club territory.[5]

According to Patrick, these unwritten rules dictated that if a member of one club was with a date, they could pass through rival territory without trouble. However, groups of guys cruising together would be challenged. The Townsmen, eager to establish themselves as "badasses," often disregarded these rules, starting conflicts wherever they could. Patrick recalled playing football against the Townsmen, with both games ending in fights.[5]

After the killing of Neil Mahan, the entire car club community united against the Townsmen. "About a week after the event, hundreds of club members converged on Townsmen's drive-in hangout," Patrick said. It was a show of force that resembled a military action. "All exits were blocked by cars, the lone security guard was disarmed and told, for his own safety, to go inside the restaurant. The Townsmen members caught there were told that they were to disband the club and if anyone was found wearing a club jacket or shirt or flying a plaque they would be stopped and their asses would be kicked each time." The streets of Long Beach were cleared of Townsmen almost immediately. "It didn’t bring the dead young man back," Patrick reflected, "but it was what all we could do."[5]

The Investigation and Arrests

The days following the attack saw a flurry of police activity. Authorities quickly arrested 20 members of the Townsmen, including prominent figures such as club president Frank Pollard and sponsor Edward T. Brick. Eddie Padilla, who confessed to firing the fatal shot, revealed that he had joined the raid in hopes of becoming a full-fledged member of the Townsmen. His remorse was evident: "I didn’t mean to hurt anybody," he said, expressing deep regret for his actions. After the shooting, Padilla buried the gun in the San Gabriel River bottom, hoping to hide the evidence.

The investigation uncovered the calculated nature of the assault. Witnesses testified that the Townsmen had planned the attack with military-like discipline, preparing for every possible outcome. They even created alibis, but under intense police interrogation, many of the young men confessed to their roles in the violence.

The Vandals' Role and the Threat of Retaliation

In the days following the tragic attack at the Moose Lodge, tensions among Long Beach car clubs escalated. The Vandals, another prominent car club in the area, found themselves at the center of rumors surrounding potential retaliation against the Townsmen. The president of the Vandals, 19-year-old Kenneth Duckworth, publicly addressed these rumors, denouncing any plans for violence. In a statement, Duckworth emphasized that the Vandals were focused on sportsmanship and competition, not revenge. "All this talk of 'warring clubs' is childish and stupid," he said. "Our guys are capable of making a fine club out of the Vandals. Some just got involved with the wrong people, that's all."

Despite Duckworth's efforts to promote peace, the fear of a full-blown "blood feud" lingered in the community. Long Beach police were on high alert, increasing patrols and conducting weapon searches to prevent further violence. The car club community was already on edge, and the Vandals had reportedly approached the Dutchmen with a warning. According to police reports, a member of the Vandals threatened that if the Dutchmen tried to meet at the Moose Lodge the following Monday, the Vandals would "come around and take up where the Townsmen left off."

The threat spurred community leaders into action. W. L. Williford, the governor of the Moose Lodge, held a meeting with car club members and their parents, urging for peace and a cessation of the violence. Williford's wife expressed the community’s growing fear, highlighting the rumors of club alliances forming to "get together to go out after the Dutchmen." This collective concern underscored how dangerously close Long Beach was to a wider outbreak of violence.

Community Response

In response to these tensions, local law enforcement and community organizers worked tirelessly to de-escalate the situation. Bob Auten of the Long Beach Police Department praised Kenneth Duckworth for his stance, calling the shooting an "isolated incident" that had been blown out of proportion and tarnished the reputation of hundreds of decent, law-abiding youths involved in car clubs. "For every bad club, there are 20 good clubs," Auten noted, emphasizing that the overwhelming majority of young men were honorable and upstanding members of the community.

The senseless violence that led to Mahan’s death ignited a wave of outrage in Long Beach. Municipal Judge Charles T. Smith denounced the Townsmen's lack of moral responsibility, criticizing the adults who had failed to guide the younger members. He emphasized the need for accountability, setting high bail amounts for the key defendants and condemning the culture of violence that had taken hold among some of the city’s youth. The community mobilized in response. Parents and youth leaders held meetings at the Moose Lodge to discuss ways to prevent further violence. Local car clubs organized fundraisers to cover Mahan’s funeral expenses, reflecting a shared desire to support his grieving family.

Revelations from the Townsmen's Diary

A Los Angeles Independent article published on May 20, 1960, provided insight into the culture of the Townsmen. The club’s official diary, a ledger filled with poorly written entries about car runs, parties, and social events, revealed a disturbing juxtaposition between youthful innocence and premeditated violence. The diary cataloged rules and rituals designed to enforce group hierarchy but did not mention the deadly attack on March 28. The naive language and focus on club activities belied the deadly consequences that would later unfold.

The Trial and Sentencing

The legal battle reached a critical point in late June. On June 27, 1960, 19 of the 20 defendants pleaded guilty to felony charges. Eddie Padilla, who had confessed to manslaughter, was sentenced to one to ten years in state prison. The other defendants, who pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit assault, applied for probation and awaited sentencing. The trial had been moved to Los Angeles to accommodate the large number of defendants and attorneys involved.

One defendant, 17-year-old Thomas Gale, maintained his innocence. As an Air Force enlistee, his future hung in the balance, with the possibility of a dishonorable discharge if convicted. The case continued to draw national attention, serving as a grim reminder of how youthful rivalries could spiral into deadly violence.

The Aftermath and Long-Term Impact on Long Beach

The 1960 Car Club War left a lasting scar on Long Beach. It served as a wake-up call for the community, highlighting the need to address the underlying issues that had fueled the violence. The death of Neil Mahan, a young life lost in a senseless act of aggression, became a symbol of the urgent need for peace and understanding among the city's youth.

Some reflect that the trial marked the beginning of the end of car club culture in Long Beach, at least as far as teenagers were concerned. The once-thriving scene, filled with camaraderie and car enthusiasm, began to wane, leaving behind a legacy shaped by both the love of cars and the sobering consequences of violence.

References

Sources

- Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, March 29, 1960

- Independent, March 30, April 1, April 12, May 20, May 27, and June 28, 1960

- The Los Angeles Times, March 30, 1960

- Los Angeles Mirror, March 30, 31, and April 1, 1960

- News-Pilot, April 2, 1960

- Press-Telegram, June 28, 1960

Did you enjoy this article?

Kustomrama is an encyclopedia dedicated to preserve, share and protect traditional hot rod and custom car history from all over the world.

- Help us keep history alive. For as little as 2.99 USD a month you can become a monthly supporter. Click here to learn more.

- Subscribe to our free newsletter and receive regular updates and stories from Kustomrama.

- Do you know someone who would enjoy this article? Click here to forward it.

Can you help us make this article better?

Please get in touch with us at mail@kustomrama.com if you have additional information or photos to share about The 1960 Car Club Murder.

This article was made possible by:

SunTec Auto Glass - Auto Glass Services on Vintage and Classic Cars

Finding a replacement windshield, back or side glass can be a difficult task when restoring your vintage or custom classic car. It doesn't have to be though now with auto glass specialist companies like www.suntecautoglass.com. They can source OEM or OEM-equivalent glass for older makes/models; which will ensure a proper fit every time. Check them out for more details!

Do you want to see your company here? Click here for more info about how you can advertise your business on Kustomrama.