The Greger Strøm Photo Collection

In the US, they had hot rods, dry lakes, and Stuart Hilborn. Norway, had Nordic Special Racers, ice racing, and Greger Strøm.

More than a hundred years have passed since Norsk Automobilklubb hosted the very first automobile race in Norway. An ice race, held on February 25, 1912, at Bundefjorden, right outside of Oslo. The interest was tremendous, and more than 10 000 curious spectators showed up at the race that cold and foggy Sunday morning. It was doomed to fail. Nobody had expected the massive turnout. Twenty club officers and seven policemen were desperately trying to control the tsunami of people that invaded the ice. There were people everywhere. A couple of cars went through the ice. The whole event spun out of control, and after an accident, a crushed upper jaw, and a fractured brain skull, it was decided to call off the race. The newspapers described it as a disappointment, failure, and a scandal, and it would take almost a decade before anyone dared to host another ice race in Norway.

Contents

- 1 Eugen Bjørnstad - "The Speed King of the North"

- 2 Petter Fabrikken

- 3 Mechanic Apprentice at Nilsen & Robsahm

- 4 First Race Car Build

- 5 New Adventures at H.C. Knutsen Autoverksted and Lillestrøm Bilcentral

- 6 The 1937 Berlin Grand Prix

- 7 Trondheim

- 8 The Greger Strøm Special No. 1

- 9 References and Sources

- 10 References

Eugen Bjørnstad - "The Speed King of the North"

By 1937 things had changed. Races were held regularly, and Norway had even bred an international superstar race car driver. "I originally took up racing as a sport, because in Norway automobiles are a luxury, not a necessity as they are in this country," Eugen Bjørnstad told a journalist from the Daily News in New York in July of 1937. Bjørnstad had put Norway on the motorsport map. The fearless kid from Oslo was known all over the world as the "Speed King of the North," and now he had crossed the Atlantic ocean to compete against thirty of the world's greatest race car drivers in the prestigious Vanderbilt Cup.

Petter Fabrikken

It might have been Eugen Bjørnstad that inspired Greger Strøm to take up racing. "Dad was a few years younger than Bjørnstad," Christian Strøm told Sondre Kvipt of Kustomrama in 2019, showing a photo of his dad sitting in Bjørnstad's ERA race car at the legendary Avus-racetrack in Berlin. Greger Rolf Knudssøn Strøm was the son of an opera singer. He was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1915, but the family moved to Oslo shortly after he was born. In Norway, Greger's parents got divorced, and the young kid moved to the small community of Stange with his mother. "There was a blacksmith in town that dad called Petter Fabrikken," Christian recalled. "Dad enjoyed hanging out with the blacksmith, and he used to spend every evening watching Petter work."[1]

Petter Fabrikken did also work on and rebuild engines, and Greger used to tell Christian about how the blacksmith could rebuild and bore an engine without replacing the pistons. Christian started working for his dad in 1964, building racing engines for Ford Norway, so he is no novice when it comes to rebuilding engines himself. "The pistons were iron," Christian continued. "So he used to sprain them. He heated them up. Sprained them, and then turned them down before they were re-installed." Christian believes it was the blacksmith that got Greger interested in cars and engines. "He didn't have much time for school," he chuckled."[1]

Mechanic Apprentice at Nilsen & Robsahm

By 1931 Greger had returned to Oslo. He was sixteen years old, and he was working as a mechanic apprentice at Nilsen & Robsahm, a Ford dealer in town. Greger rented a dorm down by Østbanen with his half-brother. According to Christian, "they shared a room, and his brother was out on the town every night." The brother went to bed late, snoring like a jackhammer. "Tired of the snoring, daddy took a coil that he wound out and put under the blankets in his brother's bed. He then put a little drop of water at the end of the coil wire. Over by his bed, dad had a little coil that he could turn and make a spark, so when his brother returned and started snoring, dad woke him up by twisting the coil. "There are shocks in my bed," he shouted out to dad. "Nah, that's bullshit," dad told him, telling him to go back to sleep."[1]

First Race Car Build

Greger's dream was to become an aircraft mechanic. That cost money, something he didn't have. Nilsen & Robsahm was a race-friendly dealer where many of the racers in Oslo at the time worked or had worked. The foreman of the shop, Cai Jensen, owned and raced a Bugatti Brescia. The expensive Bugatti inspired Jensen to build a cheaper race car on a shortened and lowered Model A frame. Greger helped with the build, and this was the first time the young kid was involved in the construction of a race car. Jensen's budget racer featured a simple, open two-seater body with a streamlined tail, motorcycle fenders, and a Bugatti-inspired grille. "It will be able to reach 150 km/t," Aftenposten wrote about it in September of 1931. Jensen envisioned himself building and selling more special racers like this. That never happened.

New Adventures at H.C. Knutsen Autoverksted and Lillestrøm Bilcentral

After four years of apprenticeship at Nilsen & Robsham, Greger went on to work for H.C. Knutsen Autoverksted in Markveien. H.C. Knutsen was the father of Birger Knutsen, a friend of Greger, and another early Norwegian race car driver. For a while, Greger did also work at Lillestrøm Bilcentral. "He lived in Oslo, and drove a motorcycle back and forth to work," Christian told Sondre. Engelhardt Løchen, another early Norwegian race car driver, was a colleague of Greger at Lillestrøm Bilcentral, and Greger used to help Løchen with his hopped-up Model A.[1]

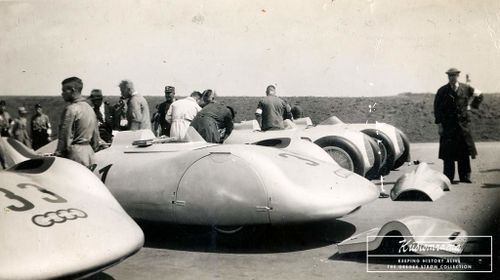

The 1937 Berlin Grand Prix

In 1933, Eugen Bjørnstad made history when he won the Lwów Grand Prix in Poland, becoming the first Norwegian ever to win a Grand Prix race. Bjørnstad's Alfa Romeo ran fifteen additional fuel tanks, and he completed the race non-stop, fooling his competitors with his ingenuity. Early in May of 1937, Norwegian newspapers started announcing that Bjørnstad was going to attend the 1937 Berlin Grand Prix. Bjørnstad was known for giving everything when he raced, so when Greger and some friends heard that he was attending the race, they decided to head down and check it out. Short on money, they rode their bikes 1000 km from Oslo to Berlin to watch Bjørnstad compete at the legendary Avus-racetrack. An estimated 500,000 spectators showed up for the event, and the Speed King of the North, with his red, white, and blue ERA, was the favorite before the race. Bjørnstad had a good start, and after a couple of laps, he had climbed his way up to a second position. Unfortunately, destiny wanted something else, and after a couple of busted tires, he ended finishing the race in 7th place.[1]

Trondheim

After the race, Bjørnstad offered his young admirers a lift back to Oslo. Back home, Greger decided it was time to build his own race car. He was living in Trondheim when he started the build, working for the Ford dealership Gaden & Larsen. "We gladly moved for fifty øre more per hour in wages back then," Greger told Ronnie Krabberød in the mid-1990s when Krabberød interviewed Greger for a story in Right-On Magazine. "I had been hanging out with my buddy Engelhardt Løchen as a mechanic in the mid-1930s. We drove a 1929 Ford roadster with a Record head, but it was only a standard car. In Trondheim, I wanted to build my own car. A real race car." [1]

The Greger Strøm Special No. 1

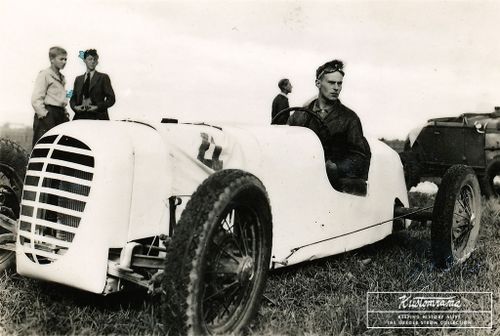

A Finish race car, built by Einar Alm, served as inspiration for Greger's build. Alm's racer featured a body made from plywood and cloth. It was very lightweight, and in 1935, it even beat Bjørnstad on an ice race at Bogstadvannet in Oslo.

Greger had bought his first car, a 1930 Ford Model A Four-Door, in the spring of 1937. The car cost 1800 Norwegian kroner. A lot of money considering the wages back then were about 1.50 kroner per hour. Wanting the race car to be a surprise, Greger built it secretly, working nights and weekends. He parked the Model A under a tarp outside Gaden & Larsen and began borrowing parts from it. The front axle was removed and modified to fit the race car frame. According to research done for the book "Bilsport i Norge," the frame was a mixture of parts. Most of it came from a Rugby, a frame Greger had bought for almost nothing. Greger wanted an underslung car, so the axle was mounted above the frame. The front axle then went back on the donor car before the rear axle received the same treatment.

A Model A engine was bored out as much as possible before the young mechanic installed new pistons, a French-built camshaft, and a shaved head. The camshaft belonged to Arvid Johansen, another early race car driver that Greger knew from Oslo.

The first test run was a failure. The camshaft provided plenty of torque, but the carburetor failed to produce as much fuel as needed. Greger solved this by modifying the jet to run faster and provide more power. Running a stock rear end and transmission, Greger estimated that the hopped-up engine produced about 60-65 horsepower at 3000 rpm.

Greger knew that a low weight would be crucial for his success. Even though he had borrowed a harder camshaft from Arvid Johansen, he knew that the engine wouldn't produce many more horses than a stock engine. Greger reduced the weight of the flywheel by 15 kg, about half of the original weight. He also ran the car without a fan and front brakes. He retained the drums, but they were empty inside. A Scintilla-magneto saved him for the weight of a massive battery. Once completed, the build weighed about 600 kg. The low weight resulted in good acceleration and a top speed of about 100 km per hour.

When Greger set out to build the Ford 4 Special, his goal was to race it at the Nordiske Mesterskap i Motorrace at Leangbanen just outside of Trondheim. Held Sunday, September 12, 1937, Greger finally revealed the secret project a week before the annual race, rolling the chassis out in daylight Saturday after work. Up until that day, Greger had secretly worked on the car after work hours and during nights, using a handheld lamp as light. There were some holes in the fence he had used to sneak back into the shop. Chairman Langnæs lived on the second floor of the building, and even though Greger used a hacksaw and a welder, not even he knew what had been going on. Seeing what the kid from Oslo had been up to surprised all of Greger's colleagues, and even the boss gave him a deserved clap on the shoulder for what he had been able to achieve.

With only one week to go, Greger now had to ask for help. He had built a structure for the firewall, but he was missing the body and various other parts. Herman Eriksen built a rough aluminum grille for the car, while a body man at Gaden & Larsen fabricated most of the body parts. Greger kept the stock radiator, but he moved it behind the front axle. The stock steering gear was repositioned toward the center of the car.

Down in Oslo, Norwegian Speed King Arvid Johansen and Erik Englestad were working on Johansen's Model A, preparing it for the race. Johansen had just won a race in Copenhagen, and now he wanted to repeat the success at Leangen. Nearly unbeatable for many years, Johansen used to brag about having at least one first-price position in all forms of racing that had been hosted in Norway in the 1930s. In 1931 he had competed in Rally Monte Carlo, returning to Norway with three Record OHV heads in his bags. Englestad was a Ford specialist that worked at Fram Motor Kompani in Oslo. He had built the engine in Johansen's Model A, and in addition to a Record head, it ran a Winfield carburetor, a Scintilla Vertex magneto, and hi-comp pistons made by Møller & Larsen.

Arvid was known for entering two cars in the races he attended. One car in the sports or special class, and one car in the standard class. The race at Leangen was no exception, and when he and Englestad left Oslo, Johansen towed Englestad in the Model A with his Ford V8 daily driver. "It was quite a ride," Engelstad told the authors of the book "Bilsport i Norge." The trip north took 10 hours, and Engelstad recalled they were pushing 110 km per hour as they drove up Østerdalen. "Seeing all four wheels on the tow car up in the air as we went over bumps was a common sight. The race car was sandblasted when we arrived, and so was I behind the little plexiglass windshield," Engelstad recalled — remembering that he didn't sleep much that night.

In Trondheim, the news about the young mechanic and his homebuilt race car traveled fast, and on the Friday before the race, both Dagsposten and Adressesavisen stepped up at Gaden & Larsen to have a chat with the debutant. Greger and his helpers were still working on the car when they arrived. The tailpiece was not yet completed, so two men were strategically placed to cover up the rear of the car in the photos.

Saturday, September 11, one day before the race, the car received its bright white paint job. Later on the same day, Greger broke the middle crankshaft bearing during a test-run. They had to tow the car back to the shop, where his buddy Birger Knutsen and a couple more friends helped repair it. A semi-finished bearing was adapted and mounted, and they finished the engine up at three o clock that night. "I had never competed in a race before, but I was calm and believed it would work out good. The night before the race, I even dreamed that I would win. I was not too sure about that when I stood on the starting line," Greger told a writer from the Early Ford V8 Club of Norway in 1988.

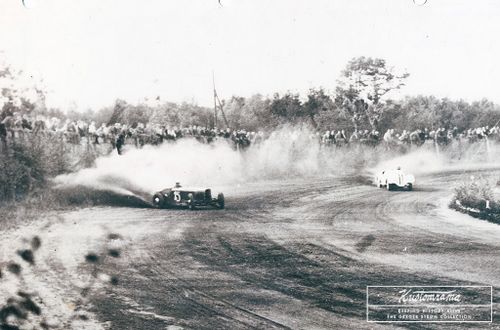

"Leangen was known as "The Indianapolis of Trondheim" back then, and the yearly race at the track was a huge event, attracting thousands of spectators," Greger recalled about his big debut in 1988. The young mechanic and his homemade race car were on everyone's lips that Sunday. Would Greger be able to give Johansen any competition at all? In addition to Johansen, Greger was also running against Odd Hagen Foss in a Hanomag Sturm Sport and Arvid Fische in a 1937 Willys Sedan. Johansen was the big favorite, and Greger overheard him telling a journalist that he planned to play a little with the newcomer at the beginning of the race before he eventually passed him by and kicked his ass.

Greger started the race in second gear. He knew that Johansen always started in second gear as well, so during practice, he had measured which gears would give him the best start. Greger's racer weighed less than Johansen's Model A, so he quickly achieved a leadership position. The next day, Adresseavisen could report that there was a lot of excitement up in the tower when the white racer shot out and maintained the lead in front of Johansen. "If he really beats Arvid, it would be a major achievement," Disponent Isberg, the President of Norsk Motorklubb, told the reporter as he was following Greger being chased around the track.

Greger knew that he had to keep Johansen behind him as long as possible to win the race. "Now comes Arvid," he kept telling himself as he was pushing the car to the maximum, "he must be tired of playing with me now..." According to the book "Bilsport i Norge," Greger didn't look back, but he could hear the intense sound from the four straight exhaust pipes that Johansen ran out of the hood side on his hopped-up Model A.

Johansen never caught up with Greger, and the young mechanic won his debut race in front of 8000 cheering spectators. In 1995, Greger told the magazine Right On that right then, it felt like he had won the Indianapolis. He completed the race in 3 minutes and 41 seconds, beating the old track record with 17 seconds. Johansen clocked in 8 seconds later. "This was beyond all expectations," Greger told a reporter after the race.

Johansen supposedly took the loss with a smile. "It was well done by Strøm," he told the reporter from Adresseavisen. Johansen also took some credit for the success, telling the reporter that Greger's race car consisted of several parts that he had sent him. "My vehicle was geared for short tracks in Denmark," he told the reporter. "I haven't had time to change gear since I arrived," pointing out that this was no excuse at all. "Strøm's racer laid as glued in the corners. And what a start that he got. Write that he kicked my ass. It's the first time this has happened in a long time." It went better for Johansen in the standard class, where he won, finishing the race at 3.58.1.

The next day, Greger had become a local hero. It is typically a “David and Goliath” story, and the local newspaper described him as a sensation. Disponent Isberg honored Greger at the award ceremony, and Adresseavisen printed his speech; "Mechanic Greger Støm, with his homemade racer, came with such an unexpected surprise. It is a great honor to see the great achievement getting its reward."

After the race, the modified axles went back on the four-door sedan again. Greger returned the camshaft to Arvid Johansen, and the engine disappeared. The race car was left rotting away in Trondheim, and still, to this day, nobody knows what happened to the famous Greger Strøm Ford 4 Special.

References and Sources

I hope you have enjoyed this history lesson about Greger Strøm. Most of the material used in this story comes from a handful of newspaper and magazine articles, Øistein Bertheau, Geir Hvoslef, and Øivind Grimso Jr.'s book Bilsport i Norge, interviews with Greger's son Christian, and a stack of photo albums that Greger left behind. Many of the photos have never before been published.

References

Did you enjoy this article?

Kustomrama is an encyclopedia dedicated to preserve, share and protect traditional hot rod and custom car history from all over the world.

- Help us keep history alive. For as little as 2.99 USD a month you can become a monthly supporter. Click here to learn more.

- Subscribe to our free newsletter and receive regular updates and stories from Kustomrama.

- Do you know someone who would enjoy this article? Click here to forward it.

Can you help us make this article better?

Please get in touch with us at mail@kustomrama.com if you have additional information or photos to share about The Greger Strøm Photo Collection.

This article was made possible by:

SunTec Auto Glass - Auto Glass Services on Vintage and Classic Cars

Finding a replacement windshield, back or side glass can be a difficult task when restoring your vintage or custom classic car. It doesn't have to be though now with auto glass specialist companies like www.suntecautoglass.com. They can source OEM or OEM-equivalent glass for older makes/models; which will ensure a proper fit every time. Check them out for more details!

Do you want to see your company here? Click here for more info about how you can advertise your business on Kustomrama.